The Auschwitz Concentration Camp stands as a haunting symbol of the atrocities of Nazi Germany during World War II. The horrors that unfolded there — systematic oppression, forced labor, and mass genocide — remain etched in the world's memory as a reminder of the damage wrought by fascism on humanity.

Yet in the Eastern Theater of the war, the Mukden (now Shenyang) Allied Prisoner of War (POW) Camp in northeastern China's Liaoning province was a chapter of history both profoundly notorious and largely overlooked. Established in 1943, this "Auschwitz of the East" was one of the most brutal Japanese-run POW camps during World War II.

The site has been preserved and become the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum.

While Auschwitz was set to carry out genocide of Jewish people, the camp in Shenyang was designed to detain Allied soldiers captured in the Pacific battlefield and force them to work to support Japan's war goals.

In the early stages of the Pacific War, the Allied forces encountered major setbacks, resulting in the fall of various Asian countries and regions to Japanese aggression and the capture of more than 90,000 Allied soldiers.

As Japan expanded its warfronts and pursued a war-sustaining tactic — namely, using resources seized from occupied territories to fuel further military campaigns, the Japanese authorities sought to exploit the POWs for labor. In 1942, the Japanese selected Allied prisoners with technical expertise and transported them to Shenyang, where over 1,200 eventually arrived.

At that time, Shenyang served as a key supply base for Japan's war machine, with large industrial zones established by the Japanese army. After being brought here, the POWs were forced to perform grueling manual labor on a daily basis, producing military weapons and other supplies for Japan.

Inside the museum, display panels feature excerpts from diaries written by the prisoners, documenting the harsh living conditions and mistreatment they suffered — acts that constituted a serious violation of the Geneva Conventions.

One excerpt was from British Major Robert Peaty, which reads: "Beating were of such frequent occurrence that one ceased to take note of them as being anything out of the ordinary run ..."

What made the POWs' daily routine even more vividly portrayed and recorded were the cartoons they drew during their internment. In a way echoed with Anne Frank's diary, which gave a personal view of life under Nazi persecution, these drawings capture the prisoners' daily moments under extreme oppression.

"As the POWs were largely brought in for military production and thus were carefully selected for their technical skills, many had proficiency in technical drawing or drafting," explained Fan Lihong, director of the museum. "That's why they turned to cartoons to document the hardships of life with humor and resilience."

One picture features the severely limited food supply, the foremost threat to the survival of the POWs. Malcolm Fortier, identified only by his assigned number — prisoner No. 1650, the sole marker of identity under Japanese control — captured this hardship in a drawing focused on prisoners scavenging for anything edible. His painting portrayed two prisoners searching for weeds and sunflower seeds to eat — just to survive, with caption noting that someone had even lost 20 pounds due to the food shortage.

A cartoon about POWs searching for anything edible, displayed at the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning province. [Photo by Wang Xingguang/China.org.cn]

Beyond the scarcity of food, the captives also faced harsh living conditions. From 1943 to 1945, the number of prisoners, mainly from the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, and France, rose to over 2,000 at its peak. With so many prisoners being shipped here, the camp became overcrowded and suffocating.

William Wuttke, prisoner No. 1475, recorded the scene of the sleeping bunks in his cartoon. It shows dozens of men crammed into a dim barrack, some climbing onto bunks, others huddled on narrow beds, leaving little space to move. As shown in the reconstructed section of the museum that recreates the life inside the camp, the wooden bunks were built in two tiers, with eight men squeezed onto each board. At times, even turning over required moving in unison with a command.

A cartoon about POWs' overcrowded sleeping bunks, displayed at the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning province. [Photo by Wang Xingguang/China.org.cn]

Replicas of POWs' sleeping bunks, displayed at the reconstructed section of the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning province. [Photo by Wang Xingguang/China.org.cn]

Life of the POWs was so constrained that obedience was their only option. Any resistance was met with brutal beatings and mistreatment from the Japanese guards.

In one picture, the cartoonist satirized such situation by depicting a prisoner facing a row of meticulously lined-up fleas. It represented the strict rules requiring prisoners ― even the fleas ― to stand at attention and report their numbers whenever inspected, so as to avoid a beating or worse.

A cartoon depicting a POW seeing a row of meticulously lined-up fleas, displayed at the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning province. [Photo by Wang Xingguang/China.org.cn]

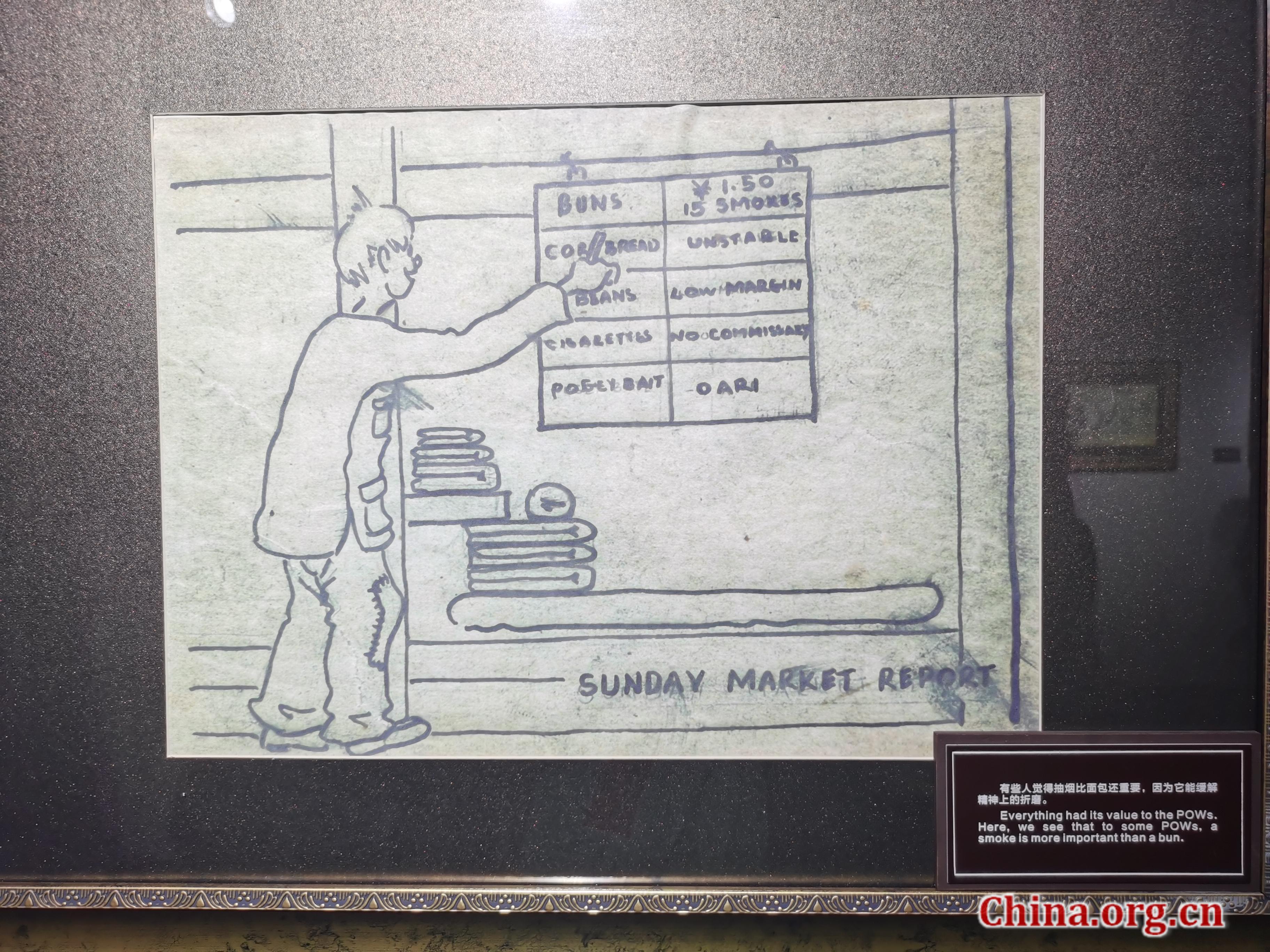

Another work reflects the mental stress that weighed on the POWs beyond physical torment, which illustrates a prisoner standing in front of what looks like a market price board. Labeled as "Sunday Market Report," the board lists items such as buns and cigarettes with prices and notes, mimicking a commodity market. The notes on the cartoon read that "to some POWs, a smoke is more important than a bun," as it could provide a brief escape from the relentless psychological strain.

A cartoon depicting a POW valuing smoke more than food, displayed at the Shenyang WWII Allied Prisoners Camp Site Museum in Shenyang, Liaoning province. [Photo by Wang Xingguang/China.org.cn]

It was not until Japan's defeat in 1945 that the surviving POWs were rescued and repatriated. Unfortunately, many perished from being subjected to freezing, starvation, disease, backbreaking labor, and severe psychological torture. The death rate reached 16% — four times higher than that of most other war camps.

"What Allied POWs experienced in the camp was an epitome of how Japanese fascism enslaved and oppressed the people around the world," said Fan. "It was a chapter of history that must never be forgotten."

Share:

Share:

京公網(wǎng)安備 11010802027341號(hào)

京公網(wǎng)安備 11010802027341號(hào)